Long fascinated by the resilience of pop icon shapes, Plummer-Fernandez expands on his ideas about illusory images, material, and copyright to generate a new version of familiar faces.

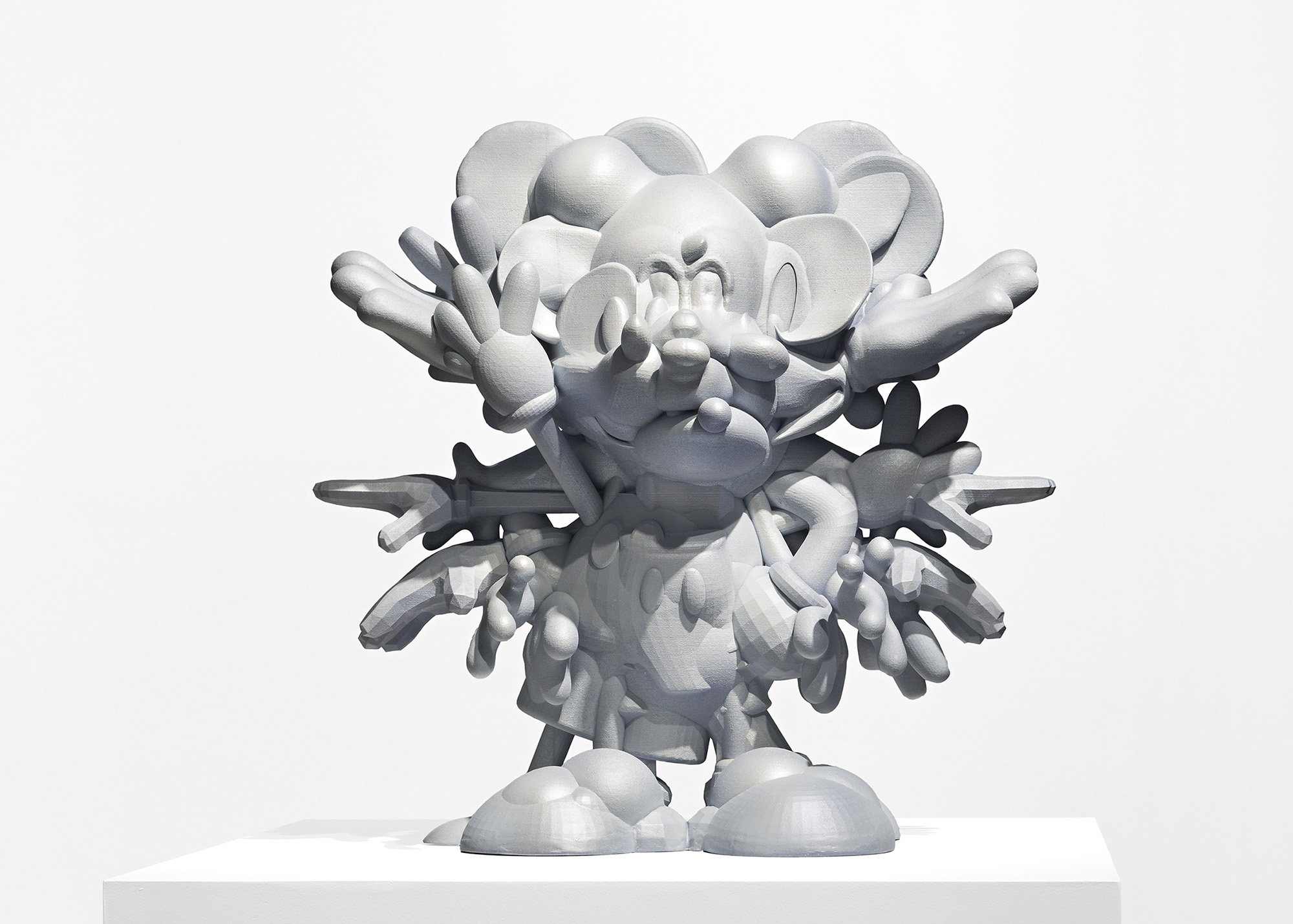

Plummer-Fernandez shows a series of new sculptures and prints that challenge our notion of an object insofar as they are works generated from the same code but represented in different forms. The four sculptures are derived from 3D models of popular cartoon characters that the artist found online and remixed in order to obtain a new version of these pop icons: “Every Mickey”, “Merge Simpson”, “Gogogogogoku”, and “Spongebool” are new forms of the popular cartoon characters.

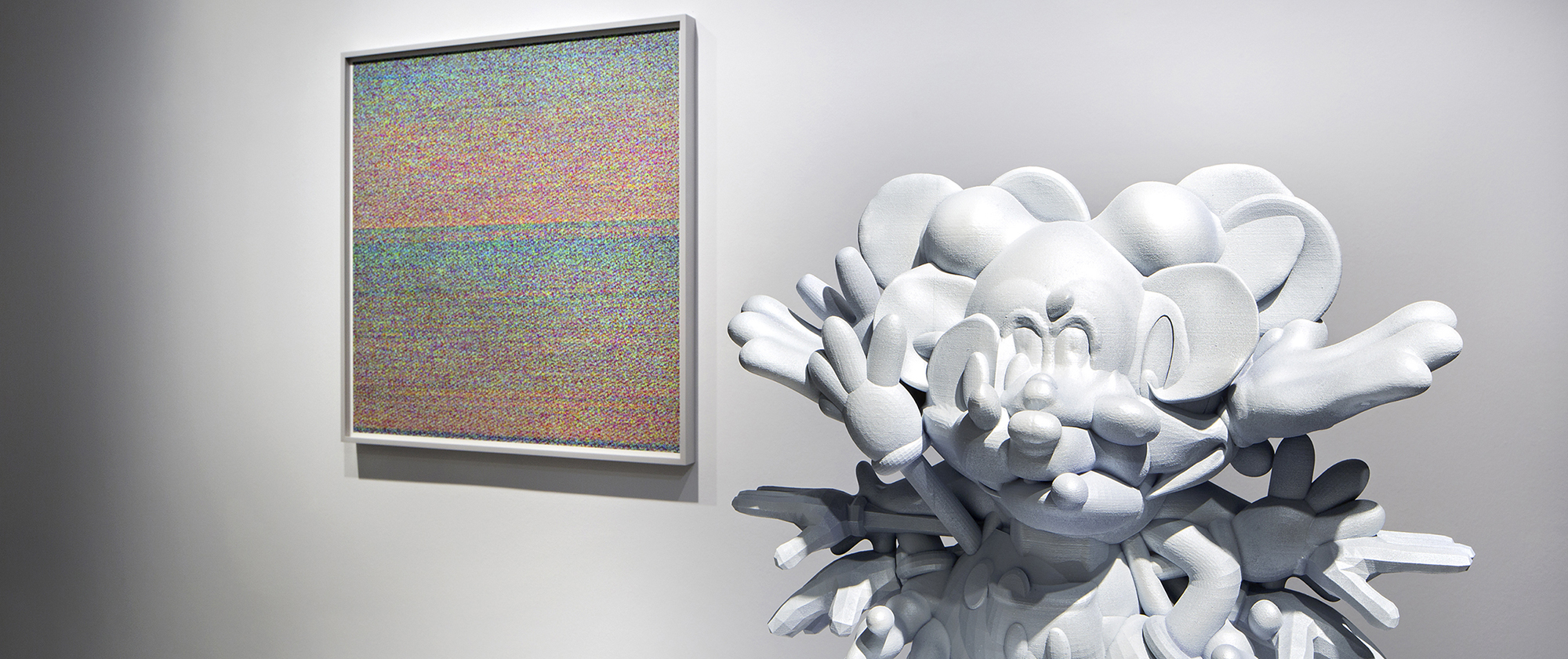

As writer Joanne McNeil describes them: “every shape seems to be contorted just to the precipice of an unrecognizable state. Any additional pixelation or pinching would submit the forms into the multitudes of another person’s imagination.” The prints are generated by converting the 3D model into an image file, a process which also serves to conceal the original source. The 3D model’s geometry is mapped onto a color range, resulting in a colorful flat surface that represents the 3D model. By creating different forms from the same code, Matthew Plummer-Fernandez questions the inner nature of an object, disputing the relationship between a genotype and a phenotype.

The exhibition challenges familiar notions of copyright and questions the point at which an original copyright ends and where a newfound freedom begins.

HARD COPY

A look at Matthew Plummer-Fernandez’s new sculptures has me wondering what might have happened if it were revealed that Rorschach were a lepidopterist at the time he was administering inkblot tests. Every shape seems to be contorted to the very precipice of an unrecognizable state. Any additional pixelation or pinching would subject the forms to the myriad possibilities of the viewer’s imagination.

Long fascinated by the resilience of Mickey Mouse’s shape—twist, stretch, twinge, or squeeze, there’s no puzzling over the wheel-like ears–Plummer-Fernandez’s new series expands on his ideas about illusory images, material, and copyright to include a new cast of familiar faces.

SpongeBob SquarePants, Goku, Marge Simpson. Even if you haven’t watched the cartoons that they come from, you have seen them on coffee mugs, cereal boxes, cell phone cases, on greeting cards and novelty valentines. They may float in the form of puffed up foil birthday balloons, as stuffed toys you might win after dunking a clown with a water gun at the county fair, as a tiled image repeating in the squares of a quilt on a child’s bed. Every example, every physical form these characters take outside of the flat drawn enclosed world of cartoons, represents a transaction, the licensing fee a merchant pays to the copyright holder.

Plummer-Fernandez’s series of sculptures is shown with corresponding prints that were made with a script he wrote to convert 3D model files into png images. The pixel colors represent coordinate geometry. The images might look like Magic Eye optical illusions but the dimensions cannot be seen by the human eye. Only when decoded will the images reveal themselves as Mickey Mouse, Goku, Marge Simpson, and SpongeBob.

It turns out that SpongeBob is a popular image on filesharing sites. The artist wonders if the cartoon character might be to this generation what Mickey Mouse was to the past. Most people under a certain age will think of Mickey Mouse as a brand logo rather than a childhood memory.

It is as remote to us as it is familiar. Every time it nears entry into the public domain, Disney, the world’s second largest media conglomerate after Comcast, foils it. They lobby and win a copyright extension. Meanwhile, the company shields its most famous character from the world like Rapunzel.

It appears on toys, of course, and pretentious, still chintzy objects: Swarovski Crystal ornaments, mock Fabergé eggs, as an option for an Apple Watch face. Mickey Mouse seems like a star from the past, like Marilyn Monroe or Clark Gable, rather than something that has ever coexisted with the internet and smart phones, or with any foot in the present. It is like a hologram version of itself.

Walt Disney chose a mouse because it was so commonplace. He saw them scurrying in the trash bins behind the studio where he would sketch. Contrast this with SpongeBob SquarePants series creator Stephen Hillenburg, a marine biologist, who was reportedly inspired to draw the weirdest creature he could think of — a sea sponge. In PlummerFernandez’s sculpture, it has raised arms reminiscent of a shruggie emoticon, its familiar surface firm rather than squeezable. SpongeBob’s dopey face is gone and instead the craterous texture circles around a hollow opening reminiscent of Edvard Munch’s The Scream.

In this series, Marge Simpson is abstracted into what looks like a fertility totem from a cult from some far off galaxy. Goku, the Dragon Ball protagonist, looks like an inverted zoetrope depicting his signature power move. Returning to Mickey Mouse, here he looks like a Hindu god with a pearlescent purple sheen. Its cold iridescence shines with all the possibilities that the Walt Disney Company doesn’t understand.

Mickey Mouse looks liberated. Like Plummer-Fernandez introduced him to a new dream world. He looks like a prism might, if prisms dispersed internet instead of light.

Joanne McNeil